Wine is subjective. The personal reactions that a great bottle provokes, often instinctive and emotional as much as educated and considered, is a big part of what makes it such a fascinating subject. It’s also a big part of what makes it so frustrating, particularly for someone who’s just getting into it. Because if everyone is entitled to an opinion, how are you supposed to know what’s good?

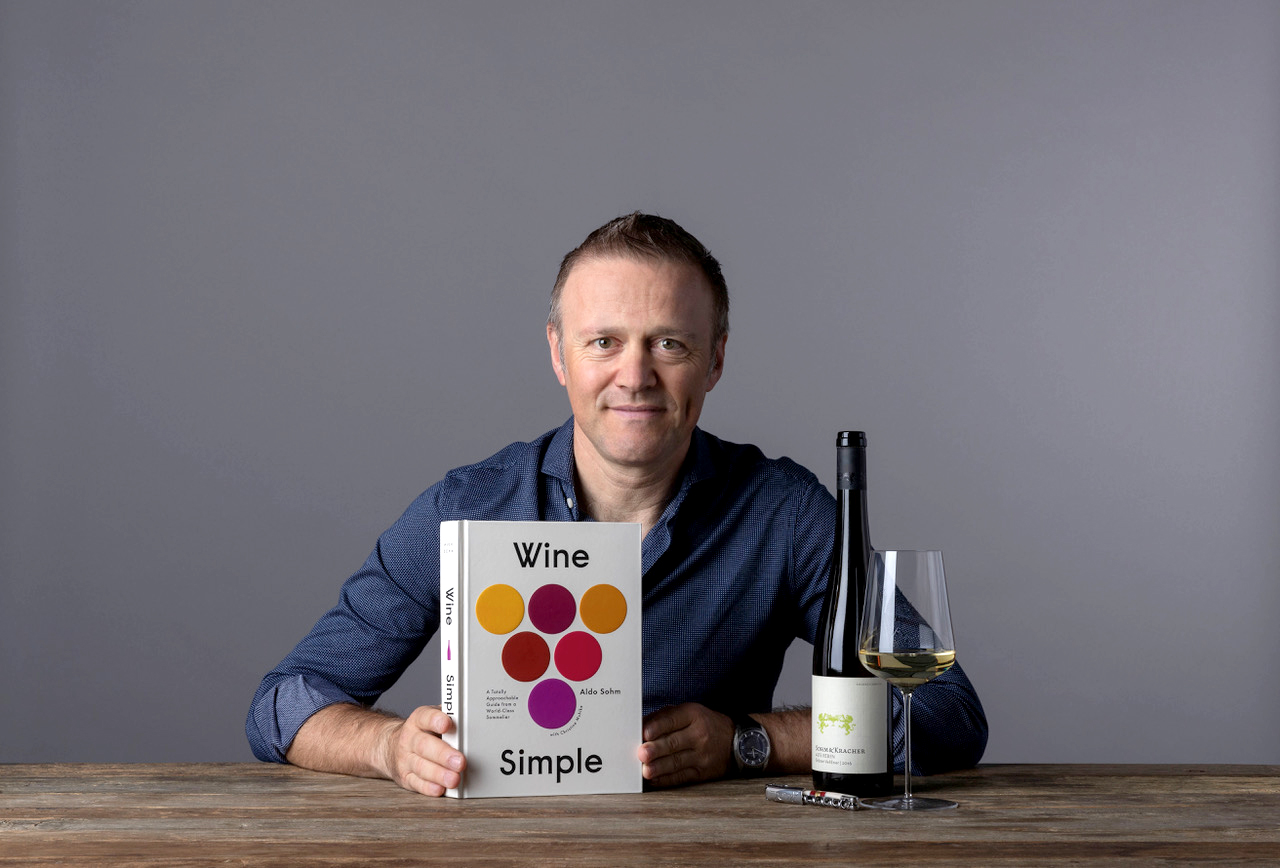

Well, to corrupt a line from George Orwell: All opinions are equal, but some are more equal than others. In other words, if you really want to know what’s good, you talk to someone like Aldo Sohm.

Sohm’s opinions are about as close as you can get to immutable truth in the world of oenology because for the past two decades he’s been regarded by his peers as one of the best sommeliers in the business.

He’s been voted Best Sommelier in his native Austria several times, bestowed the same honor in both New York, where he has lived since 2004. He runs his own eponymous wine bar in the city, which Forbes has called “Culinary Nirvana.” It’s right next door to the legendary Michelin three-star restaurant Le Bernardin, where he is also the wine director. And if all of that wasn’t enough, the World Sommelier Association named him the best on earth in 2008.

It’s a compelling list of credentials, but what really makes Aldo the man to go to is not just his list of accolades, it’s his personality. He is approachable and generous with his knowledge, while also being quick to laugh and visibly passionate about what he does. It makes him the perfect guide for anyone wishing to venture off the beaten path of familiar brands and traditional varietals.

Best of all though, from our point of view, is the fact that Aldo is also a keen cyclist.

CYCLNG OFFERS A UNIQUE PERSPECTIVE

“I did a trip recently with friends and we cycled to vineyards,” says Aldo when we talk, just before the first edition of his very own inGamba trip, which combines the best of Tuscan cycling with his decades of wine knowledge.

“The challenge was getting them all to spit at the first tasting, because too much wine and cycling is not good! There was just one exception, when the winemaker opened a bottle from 1958, we just couldn’t bring ourselves to waste any of it.

“Anyway, my friends are still raving about that trip. When you cycle through a vineyard, it’s very different to just driving past. You can smell the air, feel the heat, you hear the birds, it’s a whole different thing.

“And if you can go around the time of harvest and taste a Sangiovese grape or a Canaiolo Nero grape and then try some wine, you understand where that flavor has come from, what qualities the different grapes bring into the wine.

“You might wonder, ‘Why do you have Merlot growing in Tuscany? What does it do?’ Tasting the fruit helps to explain that part.”

LONG CONNECTIONS

Curating a trip that explores Tuscany’s rich wine culture, and the myriad different styles of wine that it produces, has long been a goal for inGamba, but it had to be with the right person, someone who saw the region’s diversity and appreciated it for more than just the big-name vineyards.

“Italy was the first wine region I studied. It might not make sense because I’m from Austria, but I grew up in Innsbruck, not far from the border, and my father used to always go to Alto Adige to buy wine. There’s a little town called Vipiteno, or Sterzing in German because it’s bilingual, and that’s where I bought my first real bottle of wine. It was a Darmagi from Angelo Gaja, 1983, which was a hell of a lot of money for me back then because I was only 22, but I’d read about it, and I was fascinated by it.

“Then, in ’92 I spent the summer in Florence to learn Italian. That was an eye opener for me because coming from Tyrol, I was only used to dry heat in the summer, but in Florence it’s so humid, it was a new experience. When we had time off, we used to go up to Fiesole to escape the heat, and I’d always carry two wine glasses with me in a shoe box. Everyone else just used plastic cups. That was when I was introduced to Chianti Classico properly, wines from Castellina, from Radda, from Panzano and Greve, and I started to put the dots together and get a proper picture of what Tuscan wine was all about.

“People often associate Chianti Classico with large brands,” says Aldo, “but I want to introduce people to smaller producers and the estates that are making really exceptional wine. Of course, it’s right to appreciate the most prestigious producers, but I want to explain to people the difference between the old school, classical mindset of some producers and say someone like Lorenza at Castello di Ama, who’s more modern in her thinking.

“The important thing is for people to understand the merits of a wine and to enjoy it for what it is. If you’re having a bowl of pasta in a tomato sauce, a simple Chianti Classico is fantastic. There’s a beauty to that simplicity. Why would you eat pasta with a Tignanello or a Sassicaia?”

RESPECT QUALITY, NOT PRICE

For Aldo, the key element of wine appreciation is recognizing and enjoying its many different attributes, rather than just learning how to give some tasting notes on an expensive bottle. It’s vital, he says, to understand the multifaceted nature of wine and to value the characteristics of what you’re drinking, rather than just the price tag. His advice is simple: “Stop reaching for the most expensive bottle every time. Try something different.

“Terroir – the landscape, the soil, the microclimate – is key and you only understand that by trying new things. For example, Chianti is not just Chianti, there’s a difference between Chiantis from Castelnuovo Berardenga and Chiantis from Greve, because Greve is at a higher elevation, so the wine is a bit finer, a bit leaner. That is the really important part of all this, appreciating how those small changes make big differences to what you’re drinking.

“You can have two wines that are high end, but there will be nuances, and you’ll prefer one and I’ll prefer the other. It’s subjective, there’s no right answer. Maybe you like wines that have a bit of Merlot in them because it comes out plusher, or you prefer something more austere, or maybe you like them both differently on different days.”

Nothing in the wine world is constant, says Aldo, least of all our own personal tastes. They can change as much, if not more, than the market trends.

“What I’ve learned from doing this job for so long is that our palettes are never constant. It changes with us. Think about it: Who really loved their first oyster? I love them now, but in the beginning? Not at all. Wine is the same, when people start drinking it, they’re not going to like a Barolo because it’s way too astringent, there’s too much going on, but once you’ve got some experience you can enjoy it and you’re able to single out the nuances that before just seemed like noise.

“Maybe we can also compare it to cycling. Riding a bike on the flat, who wouldn’t love that? But if your first ride is up the Stelvio, it might also be your last!”

UNDERSTANDING CHIANTI

“In the US in particular, Chianti Classico was seen as mass produced stuff until quite recently. Now, there’s more interest in quality producers but the best ones are still not well-known. That happens often in wine, an area shifts its focus or the public gain a different understanding of it.

“The same thing has happened recently with Albariño in Spain, it used to be known as supermarket wine but now it’s a different story. Beaujolais used to be dismissed as thin, skinny wine, but now it’s expensive.”

And how would he define a Chianti Classico?

“What makes a Chianti? For me there’s often a cherry component, and usually some almond too. The acidity also has a freshness to it. It depends what varietals you add to it, but in my opinion, Sangiovese can be very sexy by itself. It’s appealing; easy to drink but at the same time complex. Some even remind me of Piedmont in northern Italy, something like Le Pergole Torte, it’s the most Nebbiolo-like Sangiovese you can have.

“Castello di Ama is very distinct. There’s a warmness in the fruit, there’s finesse, elegance, to me it has Lorenza written all over it. That’s something that will often happen with great wines, they reflect the personality of the producer.”

TIMELESS CLASSICS

“Producers will always experiment a little, but if you can charge top dollar for a bottle it’s better not to experiment too much! That can hold some people back a bit, for example in Burgundy, with the prices they get they’ll never mess around too much, there’s an economic imperative there.

“On the other end of the spectrum, “natural wine” is a controversial topic, and it’s often misinterpreted. A lot of it is a tribal argument, too, it’s more about personalities than it is about wine.

“I think there are some producers in Tuscany who are very traditional, they intervene with the wine very little and to my palette, they could almost be considered as “natural” wines, but if you give it to someone who is evangelical about the “natural wine” movement, they’d disagree. The term itself is misleading, in my opinion.

“Personally, just because a wine smells like kombucha and has a different flavor profile, that doesn’t make it a good wine. If that’s the flavor you’re looking for, why not just drink kombucha? If nothing else, you’d save yourself a lot of money.

“That’s not to denigrate all those producers. They’re becoming a lot better and in 2020 I spent a lot of time researching the best producers because there’s a chapter about that topic in my book. But the fact is that some producers were able to sell an awful lot of screwed up wine just because it was labelled “natural.”

“If a restaurant burns your steak, they can’t just relabel it and say they meant to do it, can they? It will taste different, certainly, it might even be interesting, but would you want to eat it again? Probably not.

“On the other side, there’s a point to what they’re saying. Spraying pesticides and adding things to the wine isn’t the answer. The truth never exists at the extremes, it’s somewhere in the middle.

“The more experience you have, you always return to the classics. If you can disconnect from the marketing, or just buying brands, with knowledge you’ll naturally gravitate towards good wine. And that’s why I’m so excited about doing trips with inGamba, because it’s a chance for us all to explore and to get a different impression of Tuscan wine.

“It’s not like driving. The bike is slow. There are no distractions, no radio or air conditioning. The moment you cycle through a vineyard, when you ride across different parts of area and you feel the heat and the breeze and the altitude, you see the effect that the landscape has on the grape, and how ultimately that effect ends up in your glass.”