“You’re Irish? I remember a game in Belfast, between Northern Ireland and Italy, back in 1958. The crowd invaded the pitch and the game was called off, but Dino da Costa scored for us. He was a foreigner, from Brazil. Anyway, what can I do for you?”

It was an odd way to greet a stranger in their 30s, but then, they say time is relative. To a man in his 70s, standing in the butcher shop that’s been in his family for almost 300 years, a World Cup qualifier from half a century ago probably seems quite contemporary.

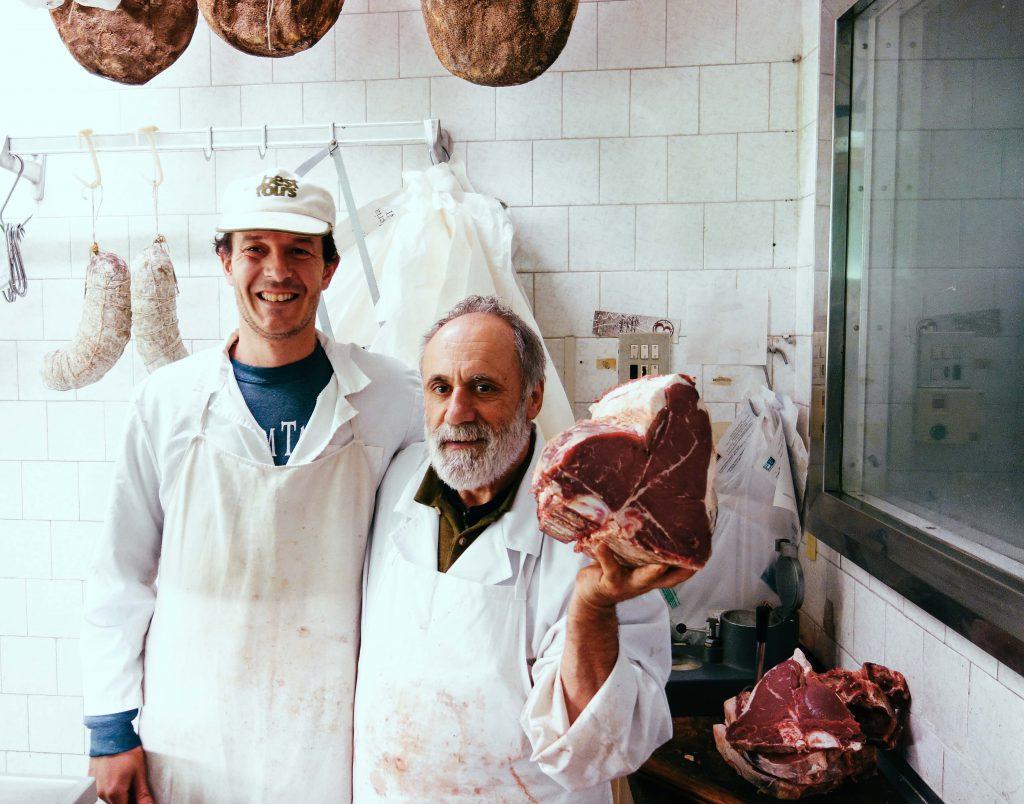

The Chini’s butcher shop is a fixture of daily life in Chianti. It has been since the 18th century. Wander in off the street and you’ll find Vincenzo Chini, an affable old man in an old white smock, behind the counter, cutting meat and chewing the fat with his neighbours, just like the generations before him.

The display counter is packed with fresh meat under cold, spotless glass. Some cuts are easily recognisable, others more recherché. There’s the famous Fiorentina steak, of course, and tripe and pork ribs. But there’s also Buristo blood sausage and a great big chunk of Testa in cassetta, head cheese, that the more senior locals relish.

There are hams and salamis and wrapped-up pieces of capocollo strung from the ceiling and beside the plain wooden bench where the customers sit and patiently wait their turn, there’s a copy of Il Calcio e il Ciclismo Illustrato, an old Italian sports magazine, with Ercole Baldini on the cover, arms aloft and smiling, resplendent in the rainbow jersey.

By coincidence, it’s from the same year as that football match. An explanation for it being there is neither ask for, nor offered. Vincenzo just says in passing that Baldini wasn’t a great champion, but that he’d been special that year. I take his word for it and flick through a ledger that records the cattle purchases that his father made in the 1960s.

Vincenzo is self-effacing about his own place in the shop’s – and the town’s – history, but when his wife pulls out a ring-binder full of clippings from newspapers and magazines around the world, he allows himself a smile. He says he’s happy that people value what he does. I’m just the latest in a long line of writers and photographers to walk through his door, because to fans of Italian food, the Chini family is important.

They represent the best of Tuscan tradition, and want to keep it that way. Don’t expect to see a Chini chain come to a town near you anytime soon. In a big city, their meticulous, considered approach to their work would be called “artisan”. Here, it’s just the way you do things. The whole family’s involved, but production is limited both by time and because in these times of industrial farming, when quantity is king, the very best meat is hard to find.

Maybe it was because of this that a while back they decided to save the Cinta Senese pig from extinction. Like them, it has deep roots in these parts. Like them, it was at odds with modernity. As a breed, it’s smaller and fatter. It tastes sublime, but it can take longer to mature, and costs more to feed for less end-product. Not a beast that was designed with profit in mind, unless the bank balance isn’t your bottom line.

“My father always told me,” Vincenzo says with a smile, just outside the butchery’s outbuildings, where they’re busy salting hams and drying sausages, “that whoever spends the most, pays the least.” Money isn’t everything, we agree, heading towards the bar next door for a glass of wine. Quality is what counts.

–